Over the past few years, I’ve been lucky enough to contribute to a remarkable seed catalog, as an editor, writer, researcher, copy editor, recipe creator, and style nag. (Yep, I’m that person.) Every year it gets incrementally better. I hope that never changes.

The Whole Seed Catalog is rooted in a centuries-old tradition — and has evolved to belong to a class of its own.

Baker Creek founder Jere Gettle first published the big seed catalog in 2014, inspired in part by the Whole Earth Catalog, publisher Stewart Brand’s counterculture classic that focused on self-sufficiency, DIY, ecology, alternative education, and whole systems thinking.

Published regularly from 1968 to 1972, and then sporadically until 2002, Brand’s catalog featured articles and essays, but it was mainly filled with reviews of an eclectic range of tools, books, and materials. For example, the first edition of the catalog, published in 1968, included books by Buckminster Fuller, a complete guide to building a tipi, and an “Alaskan sawmill,” a contraption that could be attached to a chainsaw and used to saw lumber.

Over its 10+ years of publication, the Whole Seed Catalog has taken on a life of its own, but we still want to acknowledge the catalog of ideas that inspired it. Creating it is a year-round labor of love, beginning with the gardeners who grow hundreds of varieties each year and the photographers who present them so artfully.

Both the Whole Seed Catalog and its little sister, the Rare Seed Catalog, a slimmed-down, free listing of our most popular seeds, also belong to a fascinating and colorful publishing tradition. And even – or maybe especially – in an era of digital information overload, the annual arrival of printed seed catalogs represents elemental pleasures: the promise of spring, dreams of abundance, and beautiful pages you can touch, turn, or fall asleep reading.

The Origin Story of Seed Catalogs

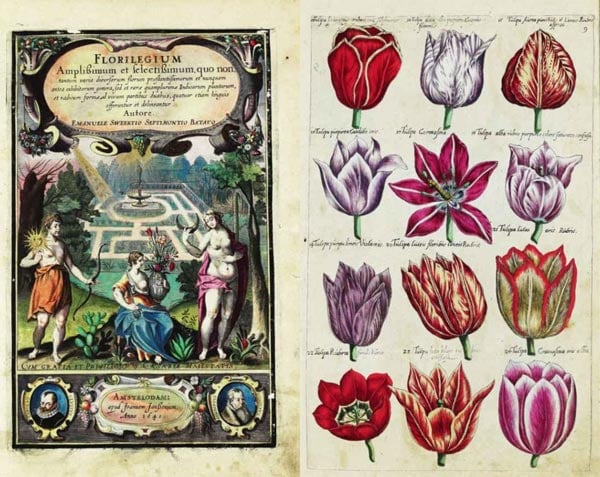

The very first botanical catalog dates to 1612, with Emanuel Sweert’s publication of Florilegium Amplissimum et Selectissimum for the Frankfurt Fair. Sweert was an engraver and plant breeder, and he served as Emperor Rudolf II’s head gardener in Vienna. Sweert’s collection of 560 hand-colored images of flowering bulbs was a listing of his available stock. His work drew on the centuries of botanical illustration that lends so much to our understanding of botany and natural history. It also predated “Tulipmania” in the Netherlands, which fueled the meteoric rise – and spectacular crash — in tulip bulb prices in the 1630s.

Seed catalogs evolved with the times, beginning with simple price list broadsheets such as British gardener William Lucas’ 1667 publication, Catalogue of Seeds, Plants & c. Considered to be the first English “catalog,” it included seeds of root vegetables, greens, beans and peas, potherbs, flowers, and trees.

The practice eventually took hold in the colonies; in 1771, American William Prince offered a list of fruit trees he was growing at his nursery on Long Island, New York. (By that time Benjamin Franklin had introduced the concept of ‘mail order’ catalogs with a list of books he offered for sale.) The early seed catalogs were basically a list of varieties, divided into types of plants, with prices.

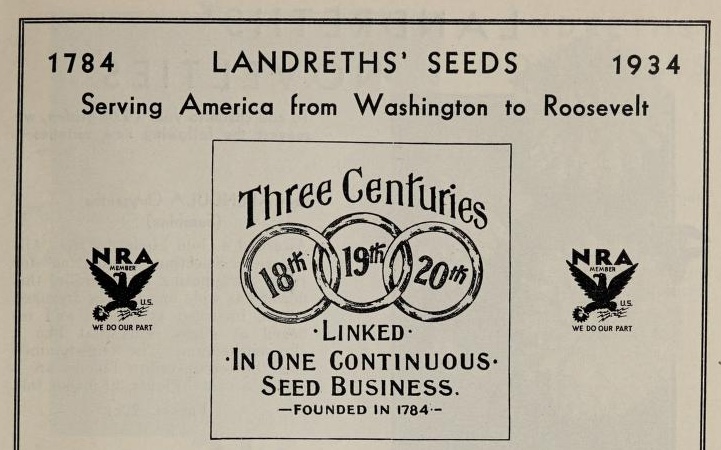

In 1784, British immigrant David Landreth established America’s first seed company in Philadelphia. Both George Washington and Thomas Jefferson bought seeds from Landreth for their estates. Landreth’s innovations were many; he introduced American gardeners to the zinnia in 1798 and the white-fleshed potato in 1811, offered the first tomato seeds to Americans in 1820, and was one of the first to publish catalogs.

Bernard M’Mahon, another early American seedsman, opened his company in Philadelphia in 1802. M’Mahon, who wrote the popular and influential American Gardener’s Calendar, published a 30-page seed booklet in 1804 – the same year that Lewis and Clark set out on their expedition to map the American West.

European settlers to America had quickly learned that the seeds they’d brought with them weren’t all suitable for the new growing conditions. Enterprising seedsmen like M’Mahon and Landreth recognized the expanding market and the chance to shape the landscape of the new nation, offering seeds from Europe, as well as varieties native to North America.

Beginning in the population centers of the East Coast – Philadelphia, Boston, New York, and places like Wethersfield, Connecticut, where James Belden founded Comstock Ferre, & Co. in 1820 – a booming seed trade took root.

As European settlement pushed west, regional seed companies opened to meet the needs of farmers, market growers, and home gardeners. By the mid-19th century, better transportation infrastructure and free mail delivery to cities and towns (rural areas would get free delivery beginning in 1896) had made mail-order catalogs the prevailing way seed companies reached their far-flung customers.

Beyond vegetables, medicinal herbs, grains, fruit trees, and grasses, many seed companies began expanding their selection of ornamentals, aimed mainly at women.

Catalogs also dispensed advice on seed starting, planting, pests and diseases, landscape and garden design, and sold tools and supplies. And, in the Wild West atmosphere of the time, they sometimes made claims about their seeds that didn’t live up to the hype.

The “Golden Age of Seed Catalogs”

The advent of chromolithography (color lithography) changed the game for seed catalog design.

While color had been part of the earlier nursery sample books that traveling salesmen used to arouse customers’ interest in plants, the process enabled vivid images to be mass produced, leading to an arms race of design aimed at capturing customers’ attention – and dollars.

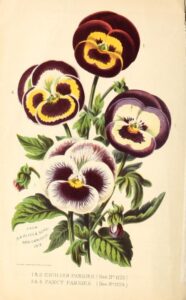

Among the first to adopt it was Benjamin K. Bliss of Springfield, Mass. His 1870 seed catalog contains a vibrant color plate of pansies.

The next year, James Vick, of Rochester, New York, included two color lithographs of petunias by his Rochester contemporary, Adolphe Nolte. Vick loved design and color, and he had worked as a printer in New York City before moving north. As the editor of the Genesee Farmer, one of America’s earliest agricultural journals, he grew circulation with the use of eye-catching floral illustrations. His gardening periodical, Vick’s Illustrated Monthly, which was published from 1878 to 1909, also leaned heavily into color. In mail-order catalogs, the company offered a chromolithograph of 30 flower varieties, suitable for framing, as an “aid in the development of floral taste.”

Black-and-white photographs came into common use shortly after George Eastman introduced the Kodak, the first handheld camera, in 1888. Landreth’s may have been the first to use photos in its 1889 catalog, publishing pictures of its Philadelphia headquarters. Kelway’s Nursery, a British company, claimed to be the first to publish color photos in 1913, using a technique called autochrome, and by the 1920s, seed catalogs were brimming with colorful design.

Seed Catalogs in the Modern Era

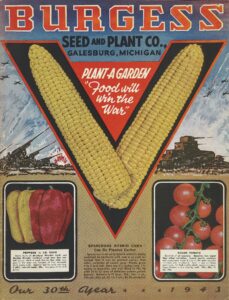

Seed catalogs are also reflections of the cultural, social, and economic forces shaping our lives. During World War I and World War II, for example, seed companies and catalogs were vocal champions of the Victory Garden movement, which urged people to plant gardens as a means of increasing food security and keeping up morale.

The development of a modern food system, with refrigerated shipping, supermarkets, and industrial canning and preservation, radically altered the landscape for home gardening.

As a result, traditional heirloom varieties, the kind you find in the Whole Seed Catalog, gave way to hybrids, developed for qualities like vigor, shelf life, thick skins, and consistency.

By the 1970s, concern was growing over the loss of seed diversity and traditional varieties. Organizations such as Seed Savers Exchange, founded in 1975 by Kent Whealy and Diane Ott Whealy, sought to revive and preserve traditional varieties. Seed Savers’ Yearbook created an indispensable resource for people eager to seek out, share, and grow heirloom varieties.

Jere Gettle joined Seed Savers as a teenager and began growing and sharing the varieties he remembered from his grandparents’ gardens. He published his first catalog – a 12-page, black-and-white booklet, photocopied and hand stapled – in 1998. The rest … is history.

Thanks to interested collectors and archivists, many excellent collections of old seed catalogs exist today, providing a critical resource for discovering and documenting the history of heirloom varieties. Our work would not be possible without them.

And although Baker Creek sells most of its seeds online these days, we can’t imagine a future without printed catalogs, those magical windows into a world of beauty, connection, and history.